This revival of Petipa’s classic at the Rome Opera pares down the ballet to its essentials trading opulent spectacle for austere elegance. Discipline dominates, passion flickers only intermittently, and the spectral beauty of the Kingdom of the Shades emerges as the production’s fleeting wonder

by Alessandro BIZZOTTO

At the Rome Opera, La Bayadère returns through a sharply modern lens: familiar, stripped to its essentials, and occasionally austere. Petipa’s 1877 classic, born of 19th-century Europe’s fascination with the Orient, has always thrived on extremes: blazing passion, jealous rage, and the supernatural spectacle of the Kingdom of the Shades.

The production by Benjamin Pech (a former principal of the Paris Opera Ballet now in Rome as assistant ballet master to the artistic director) at the Rome Opera House preserves the skeleton of Petipa’s masterpiece while paring down its visual opulence. The sets are daring yet at times overly minimalistic – copper discs, gauzy drapes – while its costumes reduce tradition to sculptural silhouettes.

La Bayadère should live on excess, on a slightly over-the-top spirit that allows the ballet to mix genres and emotions in a compellingly direct way. Here, however, it is occasionally chilly and always disciplined; beauty abounds, but narrative warmth and emotional immediacy can feel just out of reach.

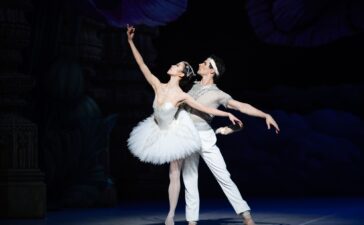

The ballet opens with the secret rendezvous of Nikiya and Solor, and here Sae Eun Park, principal of the Paris Opera Ballet, is simultaneously captivating and somewhat puzzling. Every line is perfect: arabesques float, musicality is flawless. Yet Nikiya’s fiery passion, the very heartbeat of this stolen romance, remains tantalisingly out of focus. Nikiya is also a character of contradictions, consumed by love and betrayal, and Park’s elegant restraint – almost aristocratic – paradoxically suits other roles better. Curiously enough, I found her more compelling a few years ago in the more complex role of MacMillan’s Manon in Paris, where her cool refinement gave way to desperation and frailty in moments of humiliation.

Paul Marque, also an étoile of the Paris Opera Ballet, embodies Solor with trademark French elegance: weightless jumps, crystal-clear pirouettes, and an air of effortless virtuosity. Technically, he is thrilling, yet the torment and the heartbreak, which are the emotional core of the character, are sometimes missing. Solor lives in a profound contrast: physically, he is one of the strongest male figures in classical ballet – a noble warrior, fearless in every leap – yet emotionally, he is fragile, spiritually impoverished, betraying his love for Nikiya as he cannot refuse the Raja’s proposal to marry his daughter Gamzatti. Marque is surprisingly unable to convey this duality on stage.

The palace intrigue follows swiftly, and the confrontation between Gamzatti and Nikiya is tense.

Susanna Salvi, principal of the Rome Opera Ballet, is magnetic as Gamzatti, her presence commanding every corner of the stage. Every gesture is alive with intent, every glance a study in authority and cunning. In the fight scene with Nikiya, her upper-body expressiveness becomes cinematic, transforming jealousy into an electric drama. The power she brings to her first variation, added by Pech to Act One, is effortlessly elegant, highlighting just how much this production depends on the sheer artistry of its performers.

Act Two follows without an interval and presents the celebrated betrothal of Gamzatti and Solor, framed by minimalist curtains and draperies – an oddly stark backdrop for a moment that should feel triumphant and rich. As expected, Marque demonstrates Solor’s virtuosity: clean, aerial, technically dazzling. Yet once again, the emotional depth of the warrior torn by love and guilt is lost in his elegant precision.

It is Susanna Salvi who truly seizes the spotlight in Act Two, radiating confidence and dominance throughout the grand pas. It is evident that the princess will get what she wants: every movement is charged with strength and poise, every step a declaration of character. Her famous variation is impeccably executed, a blend of technical brilliance and dramatic authority: not merely a display of virtuosity, but a commanding statement of Gamzatti’s will and ambition. The coda flows with an effortless fluidity, each Italian fouetté and fouetté en tournant executed with apparent ease, underscoring her determination and making her the undeniable force at the heart of the production.

The ballet’s tragedy reaches its peak with Nikiya’s death. Park’s final variation is haunting in its purity, a vision of line and form that trembles with delicacy. When Park dances, Salvi’s glance – knowing what is about to occur – is almost chilling. Her triumph, when the snake she concealed among the flowers bites Nikiya, is controlled yet unmistakable.

At the same moment, Marque appears more like a forlorn, drenched puppy than a broken man: the heart-wrenching soul of Solor remains a whisper rather than a roar.

Finally, the Kingdom of the Shades arrives, timeless and hypnotic. The enormous painted opium poppies lend a surreal, hallucinatory beauty – indeed, it is under the influence of opium that Solor dreams of meeting Nikiya among the ghosts of dead bayadères.

Even stripped of Petipa’s full theatrical richness, the choreography and Minkus’s music create a spectral, dreamlike world. Ghostly bayadères drift from behind gauzy curtains, their procession measured and otherworldly. The giant poppies are perhaps the production’s one genuine visual coup, where the iconic minimalism finally succeeds.

Again, in Act Three, Park’s paradox becomes evident: she often dazzles most in roles conceptually distant from her natural temperament – besides Manon, I think of her Kitri in Paris, a role requiring both comic timing and vivacity, and one in which she excelled. As Nikiya, in a part closer to her technical comfort zone and suited to her lyrical qualities, the forbidden heat of love is never fully ignited. Yet to Sae Eun Park’s beauty and technical assurance, almost everything can be forgiven, as she crosses the stage as a luminous, hieratic vision.

An unmistakable austerity lies at the core of this Bayadère, a visual diet that can hardly compete with the sumptuous luxury and opulence of other landmark productions of the same ballet. There is a strange magnetism in this restraint, a quiet seduction in which the ghosts of Petipa’s excess haunt a stage pared to its essentials, but it ultimately leaves the audience suspended between admiration and longing – intrigued, perhaps, but aware that this production comes wrapped in a certain visual frugality.